The Difference Between Creativity and Ideas

Have you said (or thought) something like this recently?

“I have plenty of ideas. I don’t need more creativity.”

“Creativity isn’t the issue for me. What I need is progress.”

“Creativity is actually my biggest problem. I’m always chasing whatever is shiny and new and never finishing.”

If so, you aren’t alone. I’ve been hearing this sentiment from writer friends and students often over the past several months.

I’ll be honest. When I started hearing these comments, I felt flummoxed. What in the world did these writers mean: “I don’t need creativity?” Fortunately, I was stunned speechless. Instead of arguing my own point of view, I listened to their explanations.

They continued:

“I need to develop my writing craft—you know, character arc, subtext, tone, things like that.”

“I’m trying to be more consistent about writing regularly.”

“I’m studying other writers’ work and learning from them.”

Okay, I thought. We’re clearly defining creativity differently. To me, creativity is the full set of emotional, intellectual, artistic, and physical skills required for starting, developing, problem-solving, and finishing a project. For others, creativity seemed more narrowly focused on starting a new project or generating new ideas.

I would have left the point unchallenged—I call it creativity, you call it something else. However, many of these same writers added:

“I don’t need to play. I need to work harder.”

Nope.

If the issue were semantics, I’d accept that creativity is a word that has lost its richer meaning because of how often it’s thrown around these days. I’d find a different word to capture the robust set of skills writers need to thrive artistically.

However, if the underlying assumption is that growth comes through clenched fists, gritted teeth, and painful effort, I absolutely must object. These writers are getting in their own way. The most likely result from “trying” to achieve something is to try for years and years. Or in other words, you spend so much time trying, you never do the thing you mean to do.

Here’s an example.

I’m not a natural actor. So, when I started my BFA in Acting, I buried my nose in books. I could have elaborated ten different ways to show a character’s thoughts and emotions through gesture. I understood the concept so well, I orchestrated my movements. As a result, I resembled a hula dancer running through planned movements rather than a real person reacting to my scene partners. My effort kept me from letting go. Over time, I discovered what that whoosh of moving into true creative space felt like, and slowly learned to get out of my own way.

I learned the way most actors do: through play.

When I say I learned through play, I mean I learned to breathe, walk, speak, memorize, and more through games. I also gained my understanding of character motivation, relationships, action, reaction, gesture, pacing and other advanced story concepts by stepping into creative space and following a game where it led. I did read many books which prepared my mind. However, on their own, the books never would have been enough. The games were where my learning experiences—from basic concepts to nuanced discoveries—actualized.

As writers, we don’t learn our craft this way.

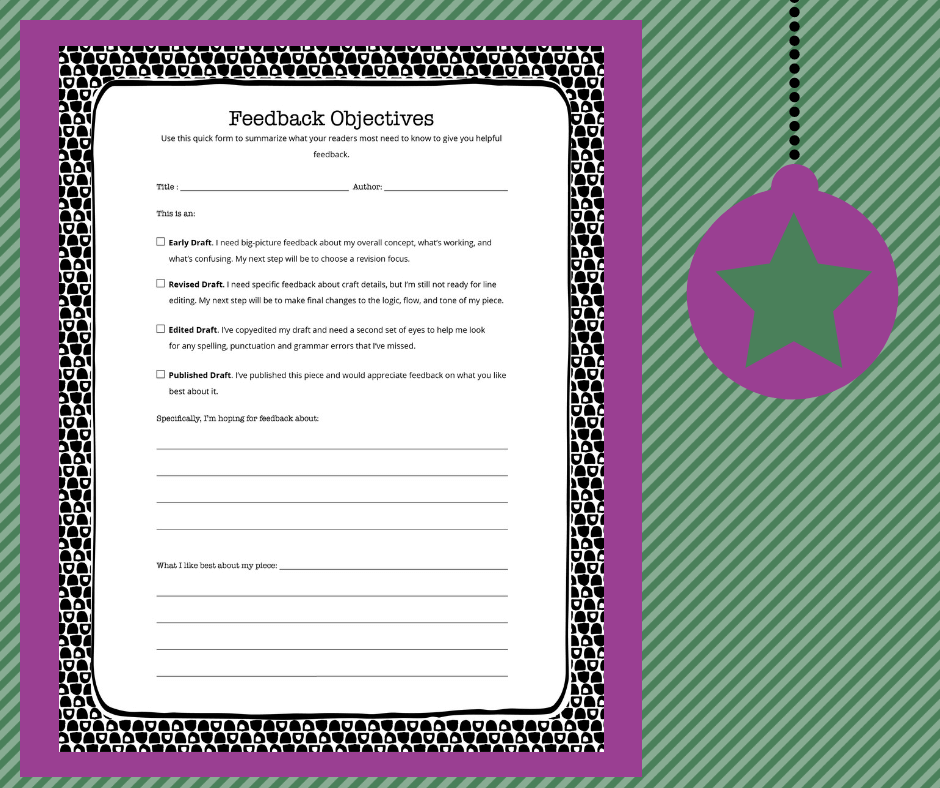

We learn to read, analyze, ask questions, think, form sentences, shape characters, worlds, and plots. We learn to think as a writer. Unless we’re very fortunate, no one teaches us to step into creative space, to let go. If we are taught to let go, it’s in the context of brainstorming or generating ideas. Once it’s time to revise, receive feedback, learn new skills, or problem-solve, we settle into our writer’s chair and let our intellect run the show.

Thus, when we hit a block, such as discovering our characters are hula dancing instead of transforming into living, breathing characters on the page, our minds kick into overdrive. We make plans, set goals, toss around accusations about all the ways we’re failing, bully ourselves into working hard.

If you’re learning writing craft, strengthening your writing consistency, analyzing strategies in masterworks, building your courage for receiving feedback, or developing other challenging creativity skills, first of all, you’re on the right track. You’re tackling the meta skills that go far beyond the current book you’re writing. In the same way that actors learn to breathe and walk, you’re mastering foundational tools that show up every time you write, whether you think about them or not. Secondly, to move these skills from your mind into your subconscious, you must practice them.

One way to practice, of course, is to write.

However, many writers are in the habit of writing with their minds. They labor over each sentence and word, rarely losing themselves in the practice or the flow of the story. Two problems emerge. First, the story lacks the energy and passion the writer knows it can have. Second, the writer’s creative skill set languishes. Stamina, courage, spontaneity, vulnerability—to name a few—simply don’t grow at the rate they might otherwise.

Another way to practice is to play.

Games offer quick application opportunities. They offer a low-resistance way into tasks that are otherwise “hard work.” When you play a game, you often spontaneously find yourself opening up and tapping into vulnerable places in your heart. In short, play takes you where you need to go quickly, effectively, and deeply.

Especially when you are frustrated, stretched for time, or blocked, I realize that opening up to play can be a stretch. To begin, I recommend choosing a simple game, giving yourself a quick win against a significant pain point.

Here are a few games you might like to try:

Tap Into the Heart of Your Story