by Naomi | Dec 8, 2017 | Creative Life

… is one bite at a time.

Hopefully you don’t eat airplanes, but if you do (and even if you don’t), check out How to Eat an Airplane by my friend, Peter Pearson. Hilarious stuff. An excellent gift idea for nearly anyone on your list.

Honestly, though. This morning, I woke up to a list that included:

- Skeleton an online course

- Revise program launch marketing materials (emails, blog posts, etc.)

- Read twelve novels in progress and provide feedback

Those tasks were only three of about twenty items. Is anyone else’s life like this? No, I take that back. I know this kind of overwhelm is the norm for most of us.

Before you send me emails explaining how I should better manage my to-do list, I honestly have been working on planting my feet in reality and putting a better system into place. And even if it doesn’t appear true, based on the evidence above, I actually have been making progress.

The real topic I wanted to write about, though, isn’t to-do lists. I’ve been thinking about how to tackle enormous projects, especially when I have more than one of them on my list–which is always. I wear more than one hat, and that means having more than one project. Most artists are in my same boat.

I’ve thought a lot about systems and processes, but the thing that has mattered most is mindset. Specifically, the story I tell myself about how I’m doing. When I’m disheartened, I work slowly. I need breaks and chocolate. And then, because of the chocolate, I need naps. If I focus on what’s working, my brain fog clears, and I can see the next right step. Or, yes… I can take the next bite of the airplane.

Recently, November ended. If you’ve been following my blog, you know I committed to revising my novel for NaNoWriMo. And … I finished! Except, I didn’t finish exactly the way I pictured finishing. The last few chapters were summarized rather than drafted. Still, the novel is one cohesive piece, and so much progress was made. Now, I could tell myself I failed, because technically I didn’t write all the way to the end. Or, I can tell myself what’s actually more true, that I kept at it, that I did the work I needed to do, and that I sent it to someone for feedback at the just-right stage.

The point is, whether I call my effort a success or a failure is up to me. And since I gave the book my very best effort in the time I had to spend, I think that calling my work a success is more healthy than beating myself up. What’s more, allowing myself to feel proud of what I achieved, rather than obsessing on what is left to do, keeps me in motion.

That plane is still there, waiting to be eaten, after all.

If you’re in a similar place, juggling many projects … I’m guessing so many of you are … keep in mind that you can definitely review your workflow, focus, and find ways to work smarter. What may be even more powerful, however, is revising the story inside your head. Don’t let it run on autoplay. Be intentional about celebrating your successes.

And keep going. One day, you’ll wake up and it will be time for the last bite of that airplane. Until the next one shows up! You love challenges, after all, so make peace with the process. That’s where you’ll be most of the time.

by Naomi | Nov 14, 2017 | Creative Life

When I write collaboratively, or for hire, I storyboard a book ahead of time. The creative limitations push me to work within boundaries, and honestly, cause me to take fewer risks.

On the other hand, when I write a book of my heart, I usually choose a question that beguiles and enchants me, which refuses to let me go. I follow my curiosity, tumbling through the drafting process, allowing the characters to be more than actors in my master plot. I find myself being surprised, challenged, pushed to consider alternate perspectives. I end up with a messy draft, but the final product is always a more interesting and original novel.

Recently, while reading Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, I found that my experience is common to other creatives. One of the many insights the book shares is that often, smaller amounts of progress are made when a question is posed to a creative and he or she works within limitations. Larger leaps happen when the creative both defines AND resolves a question.

When I think about it, this reality makes sense. Once twenty people have identified the fact that we need a book that shows us what happens when x meets y… the eventual books written may end up having many similarities. However, if the question is one most of us hadn’t yet asked, the resulting book is likely to push us to think in startling new ways.

The reality of this in my own writing process is that revision feels like untangling a delicate chain. I find a starting place and work to loosen one knot, only to realize that I’ve created another. The line from beginning of project to end is not straight or predictable. And yet, the unpredictability of this approach, the joy of discovery, the fact that I learn and grow through the writing, makes the struggle worthwhile.

I believe the artist’s job is to spend time wrestling with questions. We aren’t required to have more answers than other people, but we do need to ask more questions. We also need to spend more time working through the questions. The more time invested, the more work that we can do. Through conversations with others, revision, reflection, and feedback, we become more of who we desire to be, and our work becomes more than what we, personally, could have made it.

Maybe it’s not the most efficient way of writing a book. However, for me, it’s the way to end up writing a meaningful book.

So, here are some questions for you. Why are we all in such a rush? What are we all missing, due to our impatience? What might be possible if we slowed down and learned to savor the process?

I’d love to hear about your revision process, and how you deal with that ticking inner clock. Share below, or tag me on Facebook or Twitter. Let’s find ways to take the time we need to make our very best work.

by Naomi | Oct 31, 2017 | Creative Life

NaNoWriMo is one of my favorite challenges of the year. Participating feels like giving myself an early Christmas present, the gift of allowing myself to prioritize my writing.

However, with November right around the corner, I realize that if I dropped everything to draft a new novel, I’d only be adding more crazy to my creative life. I don’t need more drafts of new novels. I need to buckle down and finish the one I’m working on.

I’m in the messy middle, with a manuscript that I’m now revise-drafting.

I wonder how many other writers find themselves in this place? For me, revision requires identifying problems, brainstorming solutions, drafting scene possibilities, making thousands of choices, and all the while, smoothing and refining as I go.

I really do wish I could use the stage-by-stage wheel that I sometimes see in elementary classrooms, where writers move clothespins labeled with their names from step to step: idea generation, drafting and on to revision. However, once I enter the revision phase, I need to bounce back and forth into all of those modes of thinking.

Wild bouncing may seem to appeal to a creative mind like mine…

It certainly is what comes most naturally. In actuality, bouncing can clog up momentum’s wheels. If I try to draft when my brain is deep in sentence-by-sentence analysis mode, drafting a few paragraphs can take hours. It truly does matter what I set out to do when I start a writing session, particularly when time is of the essence. Structure is absolutely needed, and yet, too much structure, and my creativity hides under the table. This conundrum–the need for structure that doesn’t suffocate–is the root of Writerly Play, the need that drove me to develop a model for mapping the creative process in the first place.

I’ve been doing a lot of research on the brain science of creativity, and have also spent a lot of time applying Writerly Play as a tool to help my students move forward with their projects. However, I’ve never documented how I use Writerly Play in my own revision process day-to-day. Aha! An opportunity to learn gain new insight.

Tomorrow, it will be November.

If you’re a writer (and in my opinion, we all have stories to tell, but that’s another topic for another day) I hope you’ve given yourself permission to prioritize your writing this month. Thousands of people participate, so you’ll be in good company. All you have to say is, “It’s NaNoWriMo, I’m writing,” and most people will understand why you need an hour or two a day to camp out in your favorite writing space. If they’ve never heard of NaNoWriMo, you can send them to NaNo’s website, and nine times out of ten, they’ll be amazed and impressed and ready to cheer you on.

I’ll be revising my draft, which will likely involve drafting 20,000 new words, and will surely involve dealing with the 60,000 words that I already have. I’m using the last day of the month as a firm deadline. On November 30, I will send my manuscript out to beta readers for feedback. No excuses.

As you can imagine, I’ll be a little busy this month, so you won’t see posts like the ones I normally write. However, I will post on the blog throughout the month about how I’m using Writerly Play as I revise. I’m curious to map a project in real time. I know I’ll learn a lot about how I think and create, and I can’t wait to look over the project at the end and see what insights I gain that might be helpful for others, too.

Ready? Let’s go write!

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave

by Naomi | May 4, 2017 | Writerly Play Activities

Visit the Writerly Play Workshop and build your revision skill set. Never heard of the WP Workshop? Learn how Writerly Play thinking strategies supercharge your creativity here.

Word after word on a page can easily lull our minds into numbness.

But when we see

word

after word

on a page

suddenly we see

differently.

A few summers ago, I took a revision workshop with Linda Sue Park. What an incredible experience! One of Linda’s strategies has become a standard part of my writing practice. She asked us to take a manuscript page and break it into lines. No line could be more than five or six words. With breathing room, it became immediately clear where prose could be tightened, where words were repetitive, or where weak verbs or nouns could be strengthened.

Somehow, when the shape of the words on the page changed, I could see my writing with new eyes.

It’s a simple but powerful tool. Many, many thanks to Linda Sue Park for adding such a transformative strategy to my bag of tricks!

Try This:

- Copy a page of your manuscript into a new document.

- Break the paragraphs into short lines of no more than six words each.

- Read through and finesse the sound, rhythm and tone of your words.

- Once you’ve revised the prose in this format, put the writing back into paragraph form.

- Do a before/after comparison. What do you notice?

I’d love to hear your thoughts and insights! Share below or connect with me on Facebook or Twitter.

by Naomi | Aug 28, 2016 | Creative Life

Today, we’re on our way to the Writerly Play Workshop.

If you’re joining this series mid-stream and wondering what in the world the Writerly Play Workshop is, you might find it helpful to start at the beginning.

If you’ve been reading along, you’re well aware that the Writerly Play Workshop is another of five mental spaces in the creative landscape of Writerly Play. I find it helpful to think of the Workshop in juxtaposition to the Studio. In fact, the Studio and the Workshop were the initial reason I realized I needed Writerly Play in the first place.

In the Writerly Play Workshop, you’re invited to think critically—developing ideas, revising, and practicing skills.

When I spend too much time in the Writerly Play Studio, my ideas spiral out of control, leading me into intriguing, but often illogical territory. When I spend too much time in the Workshop, my work bogs down under the weight of my critical eye. When I start wondering why I’ve poured my heart and time into a project that I’m starting to despise, I know I’ve been in the Writerly Play Workshop too long.

However, the even more disastrous situation for me was that I had knocked out the wall between the two rooms. My inner critic had clear access to throw darts at my idea balloons. In retaliation, my wild creativity tangled my outlines into rats’ nests. Something had to be done.

That’s why I recommend that you firmly close your Studio door, and march down the hall at least three or four doorways before you choose the best place for your Workshop. You need to be able to move between the rooms, but there should not, not, not be a trapdoor between the two.

So, what kind of doorway will invite your logical, analytical self out to play? Maybe you need a sleek fingerprint keypad, or a rubix cube puzzle lock. Choose the doorway that’s best for you, and then move on inside.

Look around. What gives your Writerly Play Workshop structure and that can-do feel?

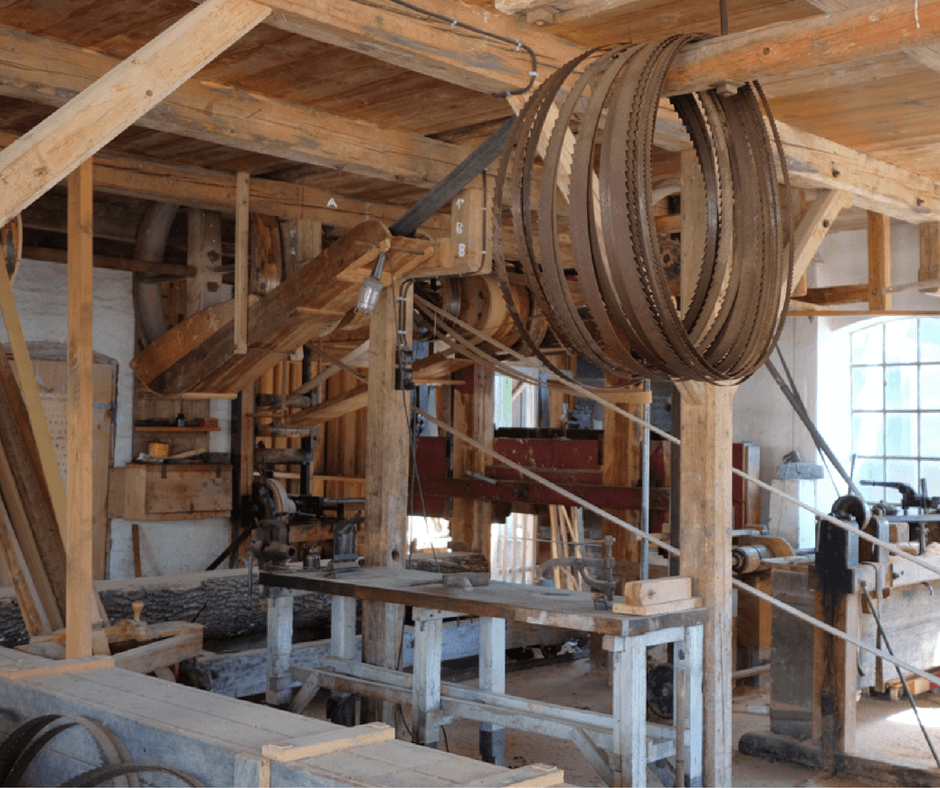

Is it a wood shop filled with power tools? A crime-scene lab fit for Sherlock Holmes? Maybe you have a diagram wall, a microscope, a storyboard, or index cards, scissors and tape.

Even if your Writerly Play Workshop is filled with sawdust and other evidence of hard work, it still ought to feel organized. Here, you want to feel clear-minded enough to focus on one problem at a time. You want to feel patient, attentive, and most of all, optimistic. You’ll be thinking analytically, poking at your ideas, moving them around, and finding connections and holes. Optimism is important so that you can look with clear eyes for elements of your project that need further attention. If you don’t believe fully that you’re capable of finding solutions for any problems you uncover, you’ll either avoid the painful truth or turn inward with harsh criticism. Neither of these stances help us in making our best possible work.

The more you engage with Workshop thinking, the more well-crafted your work will be.

The core skills in the Writerly Play Workshop include:

-

Mapping a Plan

-

Structuring Ideas

-

Observing Closely

-

Practicing Strategies

-

Revising and Rethinking

-

Fine-Tuning

In order to play to your strengths while thinking in these ways, what tools, strategies or supplies ought to be in your Workshop? What tried-and-true strategies do you have? What kinds of tools or activities would you like to seek out?

Add to your toolkit or list. And if you’d like to explore some additional possibilities, here’s my recent list of Writerly Play Workshop tools and strategies.

What do you notice when looking at the Studio and the Workshop in juxtaposition? Do you have enough distance between these two mindsets in your creative process? Are there areas of potential growth for you in developing skills in one space or the other?

SaveSave

SaveSave